Why Is It Hard for Liberals to Talk About 'Family Values'?

Racial tensions, a fear of appearing judgmental, and the sexual revolution ...?

Are "family values" a taboo topic for the left? For one thing, there may be a language problem. "Family values terminology is so closely connected to the 1980s and Jerry Falwell-esque way of framing it -- it's an immediate turn-off," said Brad Wilcox, the Director of the National Marriage Project at the University of Virginia. "You should be talking about a 'family-friendly agenda.'"

True, for those who lean to the left, the phrase "family values" tends to bring back uncomfortable memories of the Reagan era and the "Moral Majority." But there's a deeper issue: An important and damaging intellectual collapse in the way the public talks about politically charged topics.

When it comes to issues like gay marriage, welfare, and abortion, liberal politicians and intellectuals are vocal and often indignant. But they're quieter about the ways that traditional "family values" are guiding their own choices. The irony is that college-educated, wealthier Americans who identify with the left are overwhelmingly raising their kids in two-parent households. This is no coincidence: Research indicates that family stability (i.e., couples who wait to have kids until they're married and then stay married) makes a difference in income equality and social mobility.

This public/private divide raises a problem: It's like stable marriage and community are the secret sauce of economic well-being that nobody on the left wants to admit to using. As Kay Hymowitz, a researcher at the Manhattan Institute who studies the relationship between family issues and economics, put it, "They are choosing that route in part because they know on some deep level that it is the way their children will be able to remain in the middle class."

At a recent Atlantic working summit on economic security, Washington Post columnist E.J. Dionne spoke about this conversational divide. "As a country, we could be on the verge of a really good discussion of this, where we acknowledge that parental responsibility matters, that how kids are raised matters, but also that there are economic causes of this. Those of us who are on the more progressive side should be willing to engage in the conversation about family, personal responsibility, and all that."

To be fair, there are some left-leaning public voices who engage with this issue. Take, for instance, David Leonhardt's recent New York Times piece on the issues driving economic mobility, which pointed to this interesting finding from a study on economic mobility:

In metropolitan areas with large numbers of single-parent families, even children with two parents face longer odds of climbing the economic ladder. That pattern suggests that a factor that the researchers were not able to measure is affecting both family structure and economic mobility -- or that family-structure patterns have effects on an entire community.

But Leonhardt and the handful of other writers who engage with these issues seem to be the exception, not the rule. "There's no question about it," Hymowitz said. Having public conversations about family structure is "much harder for the left. The left is very much defined by questioning tradition, for good reasons and bad reasons."

So what makes this conversation so hard for the liberal community? For one thing, religion adds a layer of complexity. Broadly speaking, religious organizations have always advocated traditional family structures -- i.e., don't have babies before you get married, and once you get married, stay married. Many on the left agree that religious institutions can play a positive role in family life -- and when people follow the mores advocated in religious communities, it turns out, they are less likely to experience poverty or commit crimes.

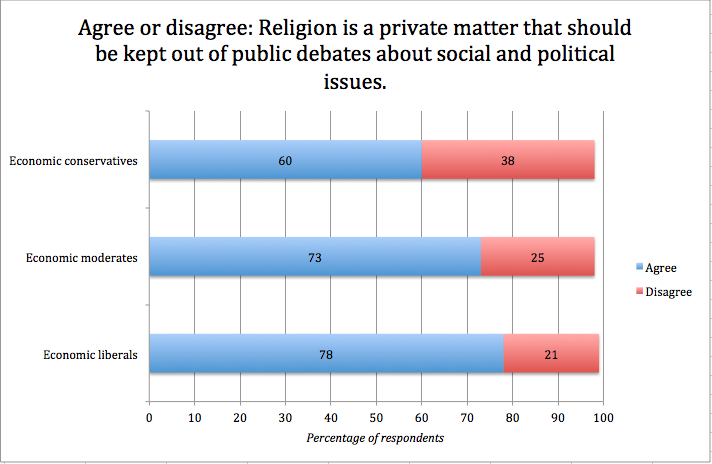

But liberals tend to break with conservatives on a key question: Whether religious beliefs and values should be part of public debates about social and political issues. In general, Americans don't think it should -- about three quarters of respondents in a new study by the Public Religion Research Institute and Brookings felt that religion didn't belong in these kinds of public discussions.

But, diving a little deeper into the data, among those who thought religion should be kept out of the public sphere, about 80 percent considered themselves liberal or moderate on economic issues like poverty and income inequality. Among those who thought religion should be included in the public sphere, the numbers of economic liberals, moderates, and conservatives were much closer.

Why do those who are center or left on economic issues want to keep religion out of the public sphere? One explanation is what could be characterized as the left's tendency to value pluralism and tolerance. The firm metaphysical framework of religion inevitably privileges certain ways of living over others, and some people are uncomfortable with that.

Another explanation is historical. "Liberals have been at the forefront of challenging all sorts of tradition as being oppressive," Hymowitz said. "That included the sexual revolution, feminism, and, of course, the gay revolution. Because the left is so identified with those themes, it becomes very difficult to propose that the break-down of the family has not worked very well, particularly for those groups the left professes to be most concerned about" -- i.e., groups like poor, single mothers.

But perhaps women need this conversation most of all. Experts believe the rising number of single mothers among lower- to middle-class women will create new challenges for those women, their children, and their communities, but the intertwined history of left-leaning politics and feminism makes it difficult for leaders to call out the problem. "Mainstream and more radical feminist groups are very uneasy with this topic, because they're concerned about questioning women's choices. They are [also] concerned about the history of domestic abuse and creating an environment where it's more difficult to talk about that and address that," Hymowitz says.

Understandably, in communities where these issues are particularly raw, leaders like pastors and politicians don't want to offend or alienate people who have made their lives work in non-traditional families. But, Hymowitz says, "Even if you're just neutral on the subject, you are still saying it's basically fine, that it's of no importance difference whether a child grows up with a father or not."

Race also matters a lot in shaping these conversations. The PRRI/Brookings study shows that perspectives among white, Hispanic, and black communities differ a lot when it comes to family issues. When asked whether the decline of traditional family structures is a primary cause of America's economic challenges, roughly 60 percent of Hispanic Americans agreed, while 60 percent of black Americans disagreed; white Americans were evenly split. Undoubtedly, this divide affects the way family issues are discussed among those communities.

Certain topics are also more or less charged in different communities. Discussions about the importance of fatherhood in the black community have garnered attention -- take, for example, President Obama's commencement speech to Morehouse College students in 2013, which drew criticism from across the media, including Ta-Nehisi Coates at The Atlantic. These reactions provide insight not because they adjudicate whether Obama was right or wrong, but rather because they point to a hard truth: It's difficult for prominent figures to find the language to talk about family issues without suffering backlash.

The result is a stifling of the conversation. The President's Advisory Council on Faith-Based Partnerships has an initiative on fatherhood, but as Amy Sullivan, a journalist who writes on these topics, pointed out, it has taken the softest of soft power approaches, making recommendations and convening conversations rather than putting the issue at the center of the administration's legislative or policy agendas.

A quiet, government-led initiative on fatherhood is the perfect symbol of a deeper philosophical divide between left and right. To use somewhat glib shorthand, the left advocates government change, while the right wants community change; the left sees structural causes for poverty and inequality, while the right sees cultural causes. In his response to Charles Murray's controversial 2012 book on these issues, Coming Apart, David Brooks summed it up like this: "Republicans claim that America is threatened by a decadent cultural elite that corrupts regular Americans, who love God, country and traditional values. Democrats claim America is threatened by the financial elite, who hog society's resources."

As is so often true, though, this philosophical binary has proven counterproductive. The research seems to indicate that problems like poverty, the achievement gap, crime are both structural (i.e., "What's the best way for the government to help reduce income inequality?") and cultural (i.e., "How are the values parents teach their children tied to kids' success? How does this relate to family structure?"). Wilcox pointed to a thought-provoking example: In a study of adolescent attitudes, teens with highly educated mothers were much more likely to predict that they would be embarrassed about getting pregnant before getting married.

Another study indicated that millennials view "being a good parent" and "having a successful marriage" as separate questions; in other words, getting married and having kids are becoming increasingly decoupled. Even though it's a tough question, it's important to ask: What will these attitudes mean for poverty, school achievement, and income inequality in the next generation?

As Dionne said at The Atlantic's working summit, "My shorthand is yeah, if you care about social justice, you've got to care about families. But if you care about families, you've got to care about social justice."

The problem is not that people on the left don't find family or values important. It's more that language, history, and ideology create political hazards, rendering family issues almost impermissible in the public sphere. As Robert Jones, the CEO of the Public Religion Research Institute, put it, avoiding family issues is a survival tactic in the face of deeply divided political camps. "If I'm a politician or organizer... on the left, it's not so much a principled censorship, but a pragmatic avoidance of the issue to keep the conversation less mired."